The Powerful History of Early Black Invention

An inventor shares what Black invention means to her

Innovations from early Black inventors made life better and safer in the United States.

Most held a desire to improve the world, though in their paths to invention, they often faced the obstacles that were systemic in the 19th century. Seen in this light, each early Black inventor’s story of success is a testament to persistence and ingenuity.

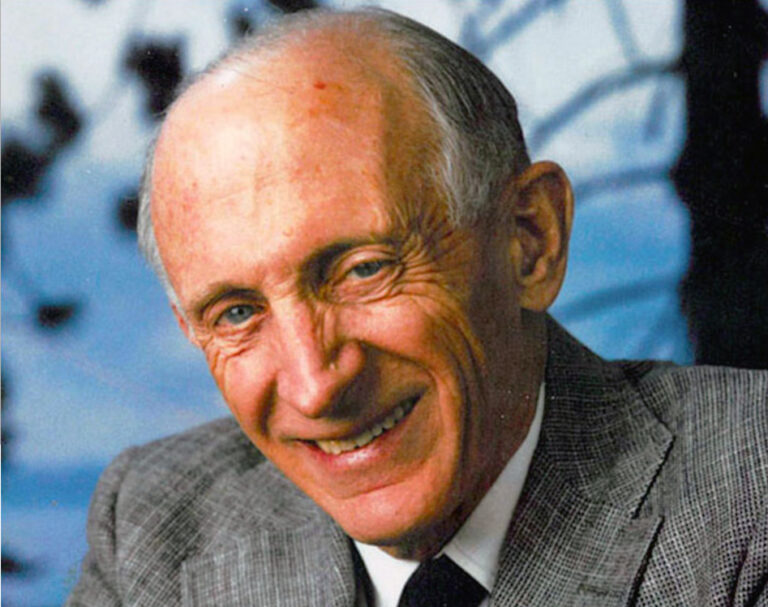

As the Executive Director of The Lemelson Foundation, Rob Schneider, wrote in his article about invention to commemorate this year’s Black History Month, “the genius of Black inventors has historically thrived despite the system, not because of it.”

At The Lemelson Foundation, we recognize that invention is only as powerful as the ecosystem that supports it. For us, that support comes from grantees, partners, and our community members like Shelley O’Donnell. She joined the Foundation in 2024 as a communications consultant, and is an inventor herself.

We recently spoke to Shelley about the history of early Black inventors in the U.S. and what that legacy means to her.

Please tell us a bit about your professional background and your own pathway to invention.

I spent nearly 30 years in newspaper journalism, briefly as a reporter, then as an editor, which I loved. I was part of two Pulitzer-Prize-winning teams as an editor at the Los Angeles Times.

Since then, I’ve directed a national corporate philanthropic foundation, overseeing strategic grantmaking and community investment, and I’ve worked at a community health center raising money and overseeing federal contracts. Add inventor to the list. In 2011, while standing in the shower, I realized my little square washcloth wasn’t reaching my back, so I put my Girl Scout sewing badge skills to the test. That’s how our first product, the Skinny Washcloth™, was born. Like many inventions, the road to success wasn’t a straight shot. There were ups, downs, and all-arounds, but today, 15 years later, The Skinny Towel & Washcloth Co.™ is alive and well with nine products. As we like to say: “We’ve got your back, front, and all over.”

You’ve been looking into the history of early Black inventors for The Lemelson Foundation. What has your research found?

The history of early invention by African Americans in the U.S. tends to mirror the history of African Americans themselves. Even though Black people were coming up with inventions to make life better and safer, there were major obstacles. Chief among them, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857, which declared that Blacks of African ancestry were not citizens. Combine this court decision with restrictive Black Codes enacted by the South in response to the end of slavery, and the picture for Black inventors was difficult.

What were the biggest roadblocks these inventors faced besides the law?

Systemic racism — and for women, racism and sexism — were major roadblocks. Other barriers came in the form of status. Were you free or enslaved? And once the Dred Scott decision was handed down, it didn’t matter if you were free. Even if you made it to that first step of actually inventing something, you couldn’t apply for a patent on your own, so you hoped that your enslaver was honest and wouldn’t claim your invention as their own.

And if you were able to get a patent, how would you get it to market? I found a 2023 quote from Rebekah Oakes, then acting historian at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), who said that, “Patent protection for a lot of African American inventors was rather difficult to achieve.”

We often hear about male inventors, but what was the experience like for Black women specifically?

While several patents were issued to Black men in the 1800s — in 1821, Thomas Jennings was the first African American to receive a patent for his dry cleaning method — women inventors would not officially rise until after the Civil War. Inventions by men tended to be outside the home (transportation, agriculture, etc.), while early inventions by Black women typically grew out of something in the household or from being in service.

Can you give us a sampling of some of these early women inventors and what they created?

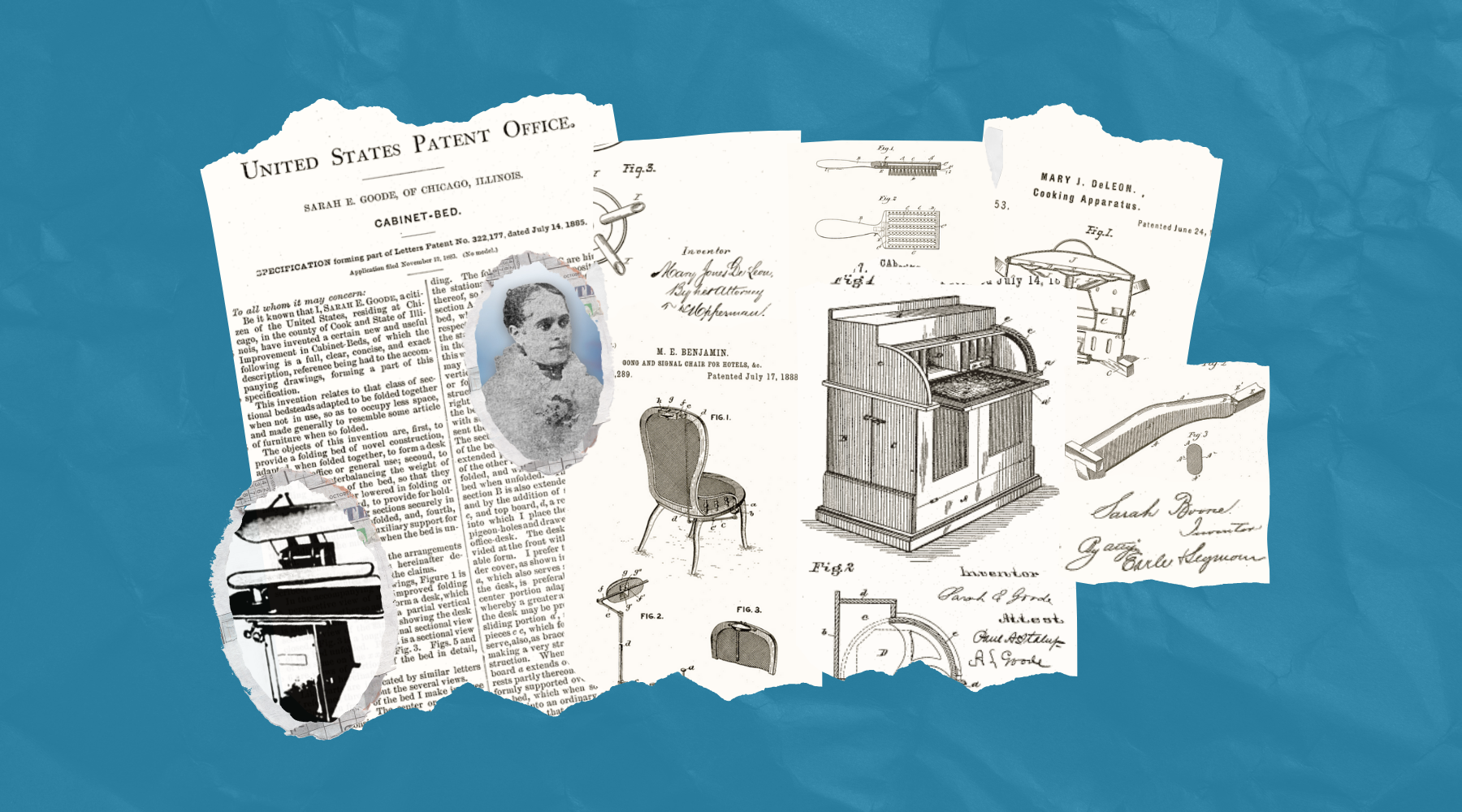

According to the USPTO, these were among the first patents to be issued to Black women:

1868 – Martha Jones for a machine that husks and shells corn in one step.

1873 – Mary Jones De Leon for “Cooking Apparatus.” Think of it as an early ancestor of today’s steam table at your local buffet.

1884 – Judy Woodford Reed for a “Dough Kneader and Roller,” which mixed dough more evenly while keeping it covered, and presumably kept it bug-free.

1885 – Sarah Elisabeth Goode for a “Cabinet Bed” that folded into a rolltop desk. Think early kin of today’s Murphy bed.

1888 – Miriam Elizabeth Benjamin for the “Gong and Signal Chair for Hotels,” which enabled guests to call for assistance.

1892 – Sarah Boone for improving the original ironing board, patented in 1858 and basically a hunk of wood. Boone added curves and other design improvements that we still see today.

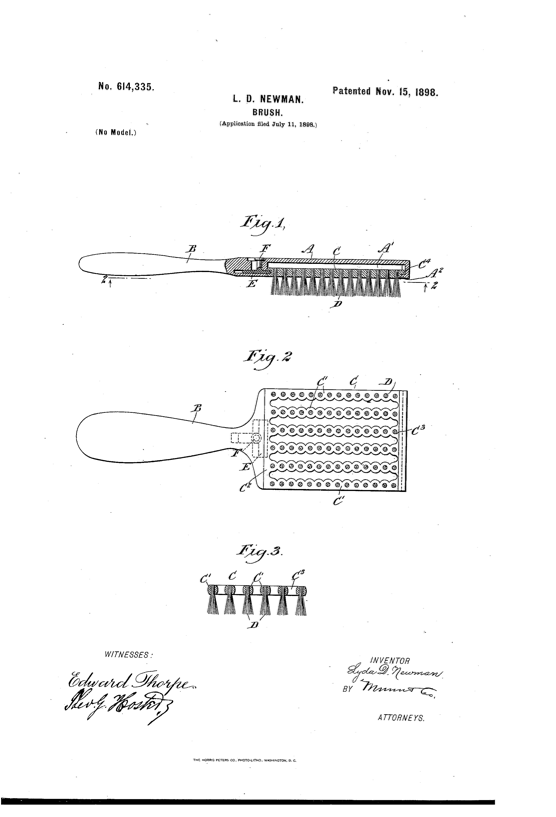

1898 – Lyda D. Newman for a hairbrush.

Why do these specific inventions matter so much today?

There are two basic kinds of inventions: the ones that you come up with from scratch and the ones where you improve upon something already in existence. These inventions are the latter, but what makes them even more exceptional is that all of these inventions are still around, and folks are coming up with alternative uses. I think Sarah Boone would be amazed to hear that I use my ironing board as a stand for my keyboard. It’s sturdy, lighter, and cheaper than a standard keyboard stand — and talk about portable!

If you could time travel back to have a conversation with any of these women, who would you pick and what would you ask?

I’ve got to go with hairbrush maven Lyda Newman. Her hairbrush is still around, and for women with thicker hair, she is a queen. I’d ask about her path from “we need a better hairbrush” to patent to market. I want to hear the details of her process and her roadblocks before she finally had success.

I know she’d be tickled to hear that when I went to buy a hairbrush last week, I thought of her as I stared in disbelief with at least 20 brushes on display! She also cleared the path for other pioneering Black women in the hair care industry. I’d also like to chat with her about her involvement in the women’s suffrage movement and the push to get women the right to vote.

What’s the one thing you want people to take away from these stories?

Know your history. History and the stories that come from it provide so much more than information. I’m very fortunate in that I can be a witness to the history that The Lemelson Foundation is making. I get to see the hard work of the team and the innovation that they bring forward, guide, and support — and that they recognize that there’s a whole world of invention out there to be discovered or improved.