Recharging the Electric Vehicle Industry

min read

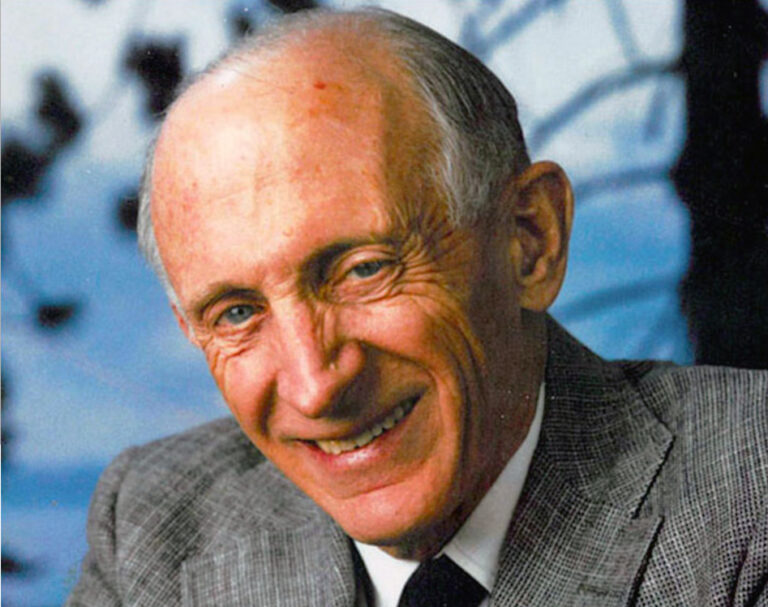

Siblings Steven (left) and Zora Chung (right) co-founded technology company ReJoule.

This sustainable startup is building a circular economy for EV batteries from the ground up

How do you make a critically important sustainable industry even more sustainable?

For electric vehicles, one of the challenges is the sustainable source itself — the lithium-ion battery. Although they are extremely efficient in storing charges and cutting back on carbon emissions, they have their own environmental impacts, from the mining of the lithium to the eventual disposal of the battery itself.

What if there was an easy way to gauge the health and life cycle of the battery, so that it could be repaired, reused, repurposed, or recycled?

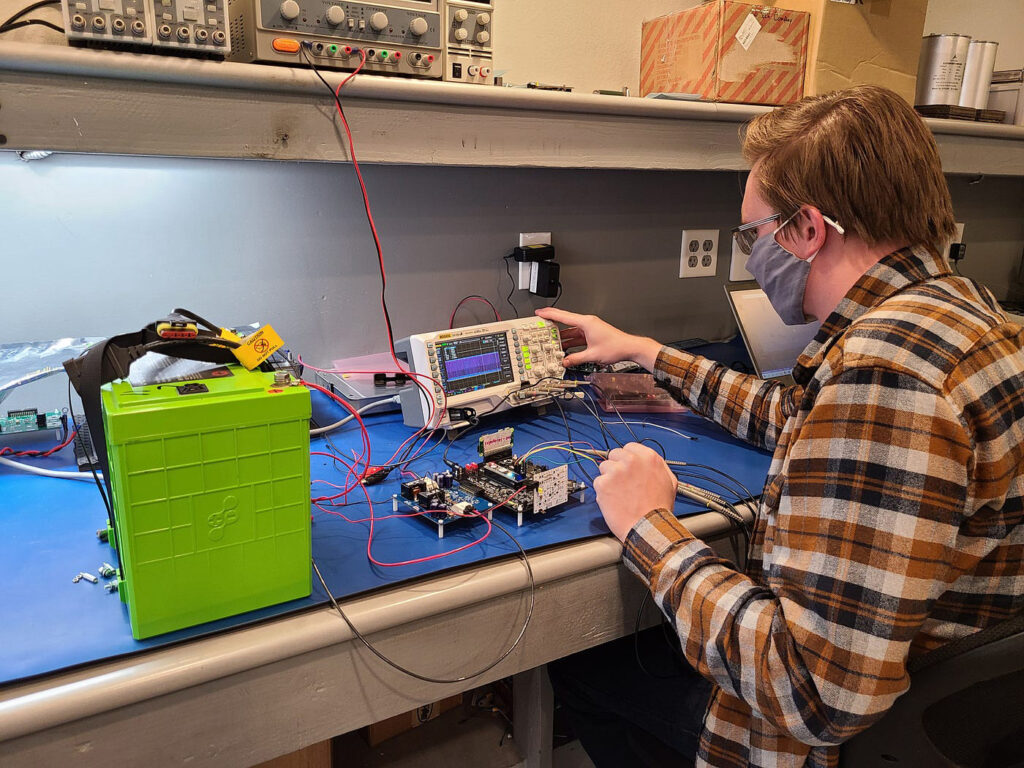

That’s a question that engineer and grad student Steven Chung asked as he was having trouble with a project to model the health of EV batteries — and the answer was frustrating. After quizzing others in the industry, he learned that it was a common issue, and one that severely limited the secondary market for batteries.

He hit upon a big problem he wanted to solve, but how could he make the leap from engineer to entrepreneur? He found the business skills he didn’t have by calling his sister, Zora Chung, who at the time was working in corporate finance at Walmart eCommerce.

The two launched a company called ReJoule with a mission to maximize the value of every battery. They would do this by developing a technology that could accurately measure the state-of-health of EV batteries, and ultimately create a circular economy for this important resource — just as electric vehicles are beginning to really pick up steam on our roads, with 1.2 million sold in 2023 in the U.S. alone.

With mentorship and training from organizations like VentureWell, they were able to build both their technology and business models, while also securing major grants and prizes along the way — including funding from the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy’s American-Made Solar Prize and its Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (JEDI) prize, and VentureWell’s 2024 Sustainable Practice Impact Award.

At left, VentureWell President and CEO Phil Weilerstein, ReJoule Co-Founder and CFO Zora Chung, and The Lemelson Foundation President and Board Chair Robert Lemelson, Ph.D., pictured after ReJoule was awarded the Sustainable Impact Award during VentureWell OPEN 2024. At right, The ReJoule team after winning the American-Made Solar Prize Round 6.

“They have so far raised over $20M in funding and created over four megawatt hours of used electric vehicle batteries for passenger vehicles, forklifts, trucks, and buses,” said Lemelson Foundation President Robert Lemelson, Ph.D., when presenting the award. “This exemplifies sustainably-based focused entrepreneurship, developing and leveraging new technologies in the pursuit of positive change.”

VentureWell recently sat down with Zora Chung to learn more about their invention and entrepreneurial journey as well as what it’s like to navigate the challenges of building a sustainable startup from the ground up.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the most important thing you want people to know about the work you’re doing?

At ReJoule, our mission is to maximize the value of every battery. The name ReJoule actually comes from the fact that it’s a unit of energy that we want to use again. If you’ve heard of the “Four Rs” — Repair, Reuse, Repurposing, and Recycling — that’s really what we’re all about. We’re enabling something that is sustainable to be even more sustainable by reducing the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the manufacturing of batteries.

What’s unique about your technology?

On most new cars now, there are sensors everywhere. A lot of things are being tracked, like what’s near the vehicle, its location, how the vehicle’s being driven. But the core thing that still is missing is how healthy the battery is. Technology like ours doesn’t really exist on the market today, and so often what we’re doing has never been seen by the world before. It’s very cool to be innovators in that sense, but also scary when you don’t know quite what to expect.

What was it like founding a company with your brother?

I definitely get that question a lot. The first thing I would say is if you’re working with anybody, the people that you’re close with do matter, but I think it’s also about the people that you have differences with. In this case, Steven is an engineer, and I’m in business by training, so we did challenge and learn from each other. But Steven and I also have a communication and relationship that nobody else would have because we’ve grown up together. And so there are certain things that can be left unsaid that might have to be communicated, thought out, hashed out with other founders, and it’s definitely something that we’ve benefited from.

What were some of the biggest challenges that you faced getting ReJoule to where it is today?

I think for any startup, there are a few things. One thing I learned very early on was don’t fall in love with your solution, fall in love with the problem that you’re solving. We had to find what that core burning problem was and who had it the most. We decided to look into automotive and energy storage as the two growing markets that had a huge need for large-format batteries. We didn’t really know people in that industry, so we had to network and figure out who and what questions to ask.

The other challenge is capital. Part of our solution required novel hardware, so it’s definitely not as easy as a few people coding in a garage. At a certain point, we need to hire more engineers, we need to buy equipment and tools for testing. Fortunately, very early on we were able to get some grants. And navigating that whole grant landscape is something that you have to really learn too.

A lot of startups go the VC route, but your initial funding was through grants. What was your decision-making process around that?

When we talked to a few of our early advisors and we looked at funding sources, they straight up told us that if you have a hardware product and you don’t have something already in market, they classify it as technical risk. So before we had proven the technology, it was nearly impossible to take private capital. But then organizations like the National Science Foundation purposely fund technical risk. Many of our early grants, they basically are shooting for the stars, not only looking for an incremental change, but a huge step change in technology, knowing that many of them might not even work. What we need to show is that we’ve thought through how to experiment, how we would use the funds intelligently, and how to listen to the market so that we would also know when to pivot.

Are there any challenges that you’re currently facing with ReJoule?

We’re starting to commercialize the technology and targeting big companies, which is a challenge in itself. You have longer sales cycles, and there’s a lot of people that you need to talk to. Once you find the right business unit, they still need to go back and get approval from the headquarters as well. So trying to basically find an optimized business model is one of those challenges.

We are in this interesting phase right now where everybody knows that there are more and more electric vehicles that are coming, and more batteries that they will have to test over time. But if it’s not happening right now, a subscription model might be hard for them to justify to the procurement team, for instance. And so we might have to do more of a pilot before we can engage in a longer-term subscription model for them.

Do you feel like your experience working for very large companies has made it easier for you to know how to work with a big corporation?

I think to a certain extent, yes. It helps me become more empathetic and understanding, especially to the folks that I call our champions, because they’re the people that brought us into the organization. They’re introducing us to their managers. they’re the ones that we’re solving that core problem for. So often I might share a model or share a presentation that tries to speak not only just to the problem that we’re solving, but maybe to the larger impact of how this would help the company at scale, basically getting right to what the ROI could be and the cost-benefit analysis.

What is something you’re most excited about that you’re doing right now with ReJoule?

We just published a white paper [available for download on the ReJoule website] in collaboration with the Automotive Recyclers Association. Aside from just supporting automakers, the recyclers are a lot of these multi-generational small businesses that will need to upgrade a lot of their facilities and training to be able to handle batteries from electric vehicles versus engines from internal combustion vehicles. Being able to support that market and employing even more new technology is quite exciting.

What we’re able to do now is actually test the battery through the vehicle’s fast charging port. So that removes the need to have the heavy-duty equipment to take the battery out of the car. Simplifying that process is exciting because that means that more people can use our technology and more people can become battery technicians.

What’s the biggest challenge facing the industry now, and then where do you see the industry in about five years?

Charging is still an issue and a question I think consumers have — not so much range anxiety as before, but just maintaining your EV and getting access to a good charger. But there’s starting to be issues about the repairability of these electric vehicles, and how you sell a used EV if you don’t know what the residual value is. We’re very excited to be able to impact that because 75% of the vehicle sales in the U.S. are from used vehicles. The sale of used EVs is really when you’re going to hit mass market.

Was there a moment that made you realize that you could be an entrepreneur, and that you wanted to be one?

That seed was planted very early on because my parents run their own business. They always felt that was the American dream, where you’re able to start something and be able to be your own boss. But the funny thing was, for my first job out of college I went to Clorox, which is a huge company that’s been around for hundreds of years, and then going to Walmart on the e-commerce side. It was at Walmart where I started working with more of the startups that we acquired. That got me reinterested, because they still had a very different mindset and mentality than being at a big company. And I learned that I really enjoyed problem solving and building.

Do you have experiences to share about being a woman and a founder and an entrepreneur in a male-dominated field?

I would say there’s a few times where there’s that whole fish-out-of-water feeling. Especially if you’re talking about batteries and automotive, you’re not going to see a lot of women in general. When I went to events, that definitely stood out. Everybody also dresses the same at these conferences — a lot of the men wore almost like a uniform. So for me I thought, why don’t I just wear a bright blue dress or a bright red shirt because then I’ll stand out for people to find and talk to me. The industry has grown a lot, but when we first started, it was quite small and it seemed like everybody knew each other. But a lot of people were very friendly, saying “I’ve never seen your face before.” They made the conversation easier, and were just curious about what we’re working on.

What advice do you give to young people or college students who want to become an entrepreneur?

I would say find a problem that you’re really passionate about solving. You need all types of people to run a business. The passion for whatever the work is, what solution you’re bringing to market, is what unites everyone.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.