How Adversity Led to a Lifetime of Engineering and Invention

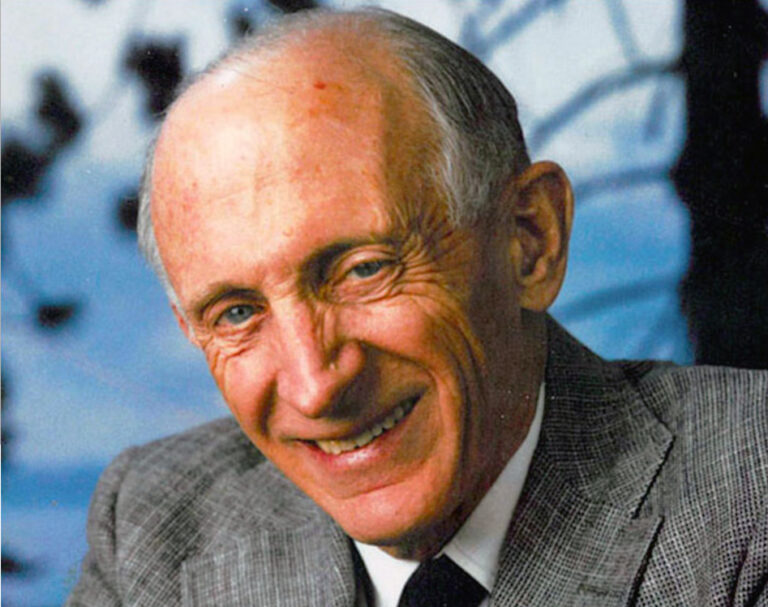

Dr. Rory A. Cooper is a veteran, an athlete and the holder of more than 20 groundbreaking patents in wheelchair and other assistive technology.

If you use a wheelchair or know someone who does, chances are it includes technology invented by Dr. Rory Cooper. A United States Army veteran, Dr. Cooper has been designing assistive technology since a spinal cord injury during his military service left him partially paralyzed.

Dr. Cooper’s work on accessibility issues has been groundbreaking, and his inventions have been life-enabling for countless people. Part of what drives him is the Army’s core value of selfless service. “I wouldn’t be true to the oath I swore if I didn’t try to correct some injustice and create opportunity,” he said.

Dr. Cooper holds dozens of patents, and last year joined the ranks of Ellen Ochoa, Nikola Tesla, and other scientific innovators when he received his own inventor trading card from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. He is also an avid athlete and Paralympic medalist. Whether he’s working with students in his lab or meeting with lawmakers on Capitol Hill, Dr. Cooper, who is also an AAAS-Lemelson Invention Ambassador, has never stopped using his experience and expertise to improve the lives of people with disabilities.

Earlier this year, he spoke to members of Congress about his concerns regarding the lack of diversity in American invention. “Homogeneity is the enemy of innovation,” he explains, noting that America would benefit from more women inventors and more inventors who are from different socio-economic backgrounds. But raising awareness on diversity issues is a process. “It takes education and dialogue and time.”

Dr. Cooper grew up in the Southern California area, noting that while his family did not have a lot of money, they had a talent for engineering that spanned generations. “My grandparents, my mother, and my father were all automotive machinists,” he said. When he was young, he applied his skills the way any kid with an engineering mind might: to building and modifying skateboards, bikes and motorcycles.

But a spinal cord injury at the age of 20 halted his mobility. Dr. Cooper had joined the Army and was stationed in Germany when a truck hit him while he was riding a bicycle. The accident ended his time in the Army and left him paralyzed from the waist down. But it was a turning point in his career.

“The VA helped put me through college,” he said. Because of his gift for engineering, Dr. Cooper decided to enroll at the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. It was there, in the rehab hospital, that he got his first glimpse of his future as an inventor. “The wheelchairs had not changed — or had changed very little — from the wheelchairs that veterans received during World War II,” he said. He began making his own chairs, and then went on to graduate school at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he discovered the field of rehab engineering. “And that launched me into continuing my work inventing things.”

Since then, Dr. Cooper has designed hundreds of assistive technology devices and has received more than 20 patents. His wheelchair innovations include the Ergonomic Dual Surface Wheelchair Push Rim — designed to relieve stress on the user’s upper body when gripping the push rim, the part of the wheelchair that users hold to propel forward — and the Smart Wheel, a tool that allows clinicians to gauge the amount of stress a push rim is causing and make adjustments.

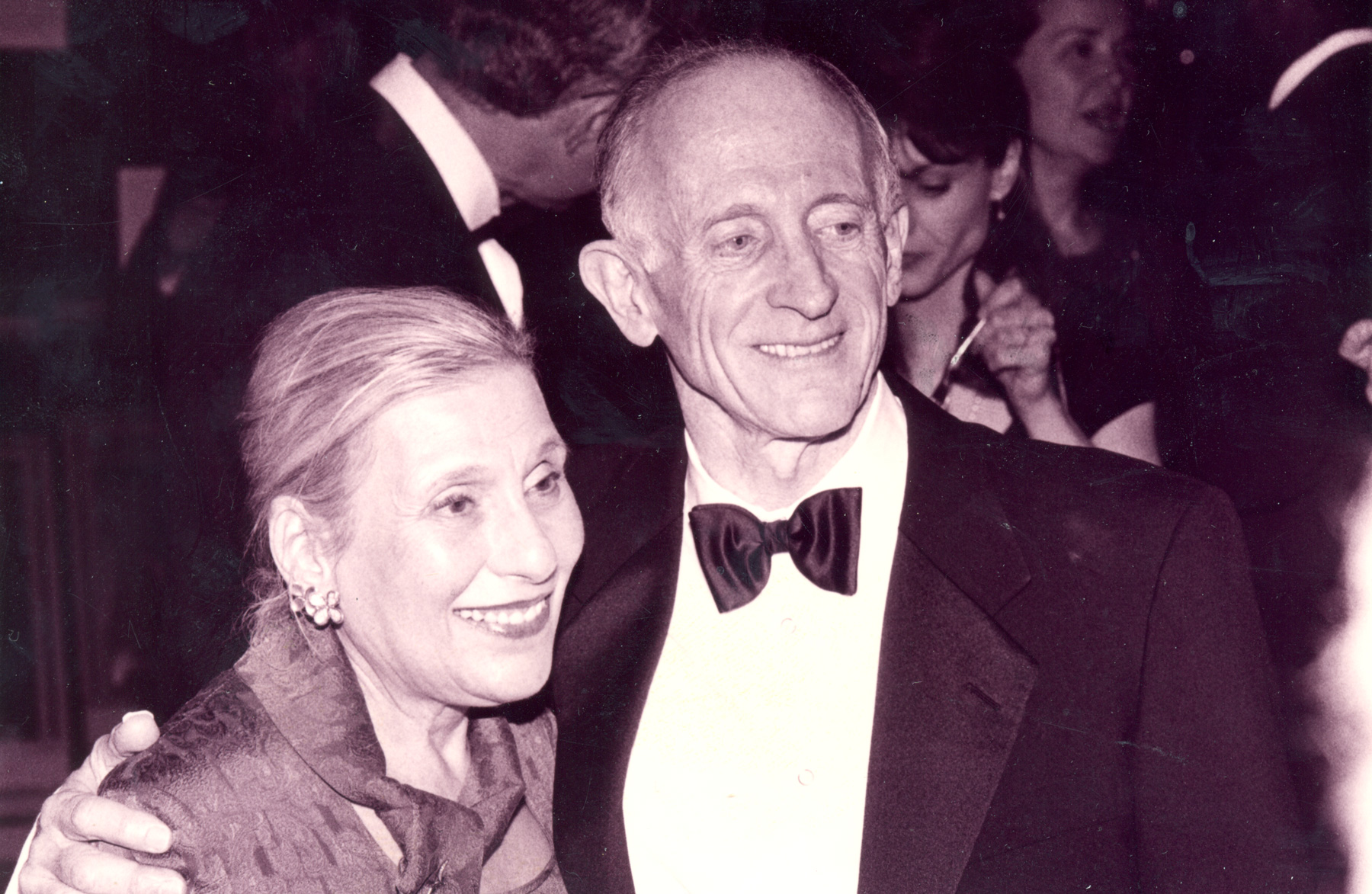

These innovations have dramatically reduced the number of people who experience repetitive strain injuries due to wheelchair use. “The rate of carpal tunnel and rotator cuff injuries decreased from about 80% to about 20% after five years of wheelchair use,” Dr. Cooper said, saving people and the healthcare system tens of thousands of dollars. But the more important measure of success in his work is people’s happiness. “My wife is a physical therapist and many of her patients use my technology. They tell her that it’s changed their lives or their loved ones’ lives. My inventions have never made me a lot of money, but I have been paid more in smiles and happy tears than most inventors ever have.”

Before the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990, Dr. Cooper, like many others, had difficulty flying with an airline, renting a car, getting a credit card, acquiring a home loan or securing a job. There are fewer barriers for people with disabilities now, though some still persist. One of the biggest, he said, centers on attitudes and perceptions. “Nearly everybody with a disability faces the challenge of how people perceive you, what you’re capable of doing. I face that to this day in various ways,” he said. “Frankly, the work that I do is in some ways a challenge to convince people that older people and people with disabilities have value.”

And for Dr. Cooper, human value — regardless of ability or disability — is paramount. “The mosaic of people in the world is what makes it so beautiful. If you start to take pieces and shapes and colors out of the mosaic, it’s not as beautiful.”

To aspiring inventors he offers this advice: Be tenacious. Be part of a diverse network and learn from other people. “They say science happens at the intersections. That’s true of invention too.”