Protecting the Planet, One Engineering Class at a Time

min read

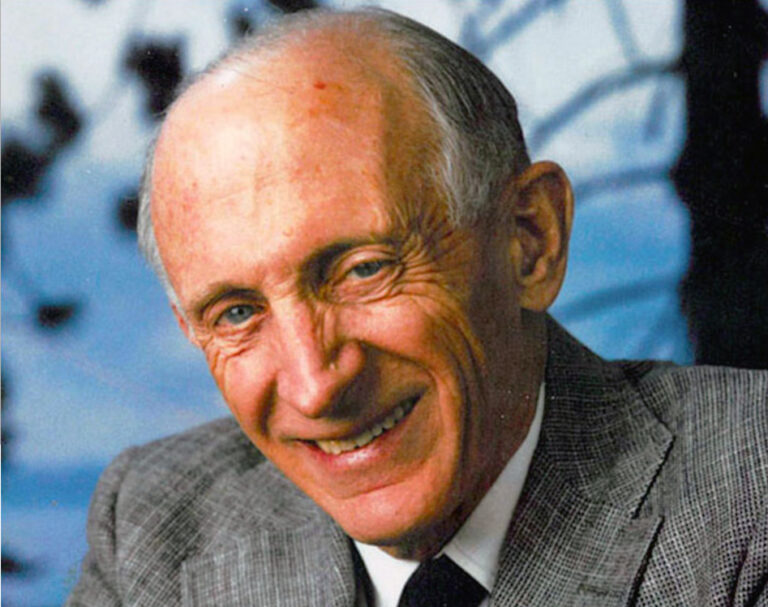

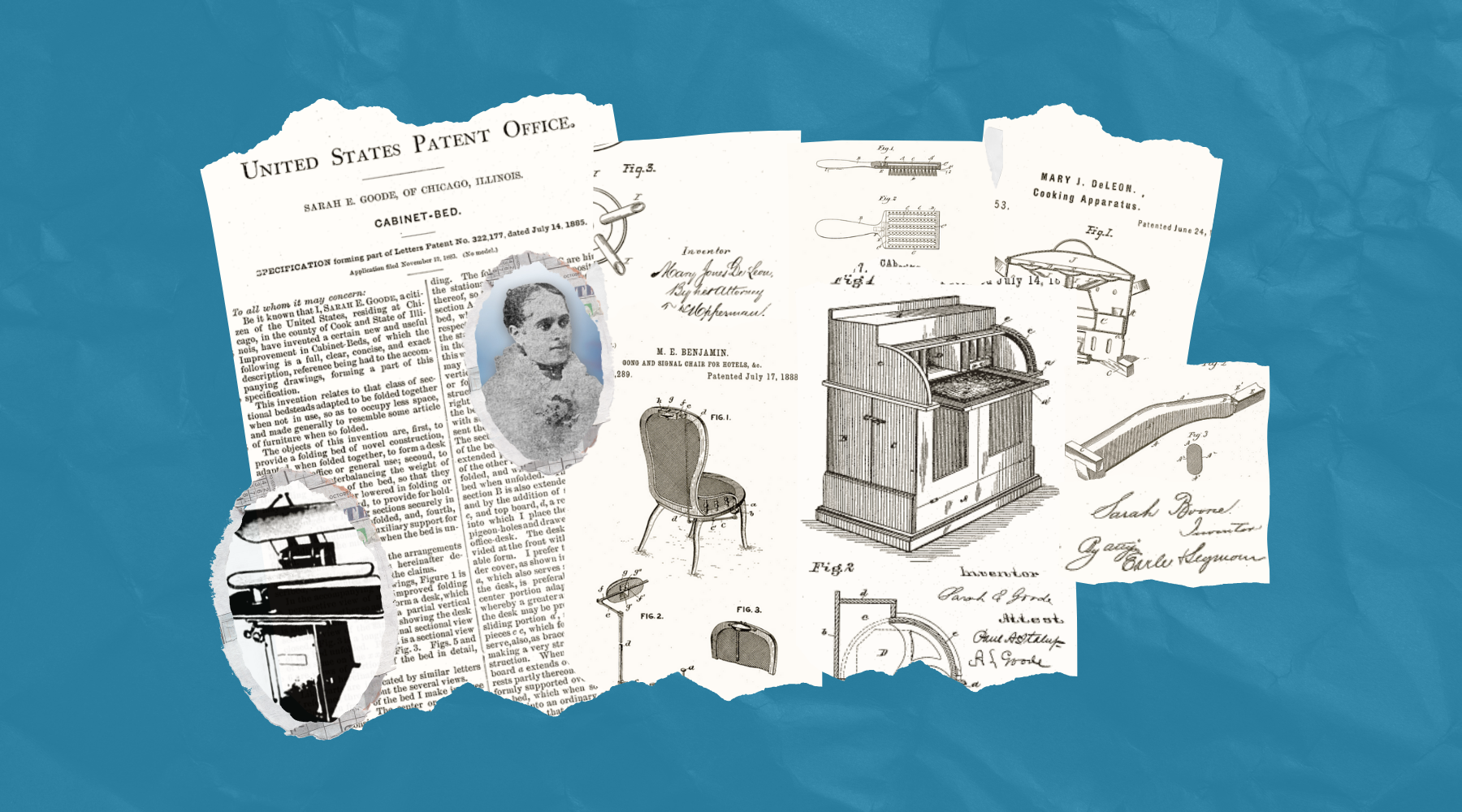

(Pictured above: Cindy Anderson conducting research in Antarctica in 2005.)

How a wildlife biologist’s unconventional career path led to a sustainability movement in engineering education

For about a decade in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Cindy Anderson spent over half of each year as a wildlife biologist studying polar seabirds. Her schedule went like this: four months in the Arctic, one month off, six months in the Antarctic, one month off — and repeat.

In the Canadian High Arctic, Anderson conducted research with a small team living in tents on an island where polar bears were regular visitors. When she wasn’t “on the ice,” she’d present at scientific conferences about the impacts of climate change she witnessed first-hand. She loved sharing her work but felt frustrated that she wasn’t reaching new audiences and that things weren’t fundamentally changing.

That was until she attended a speaking event about biomimicry, a field of study she realized could connect her knowledge of the natural world to human-created design. From that moment of discovery, she’s dedicated the past 20 years of her career to teaching various disciplines about sustainability and design.

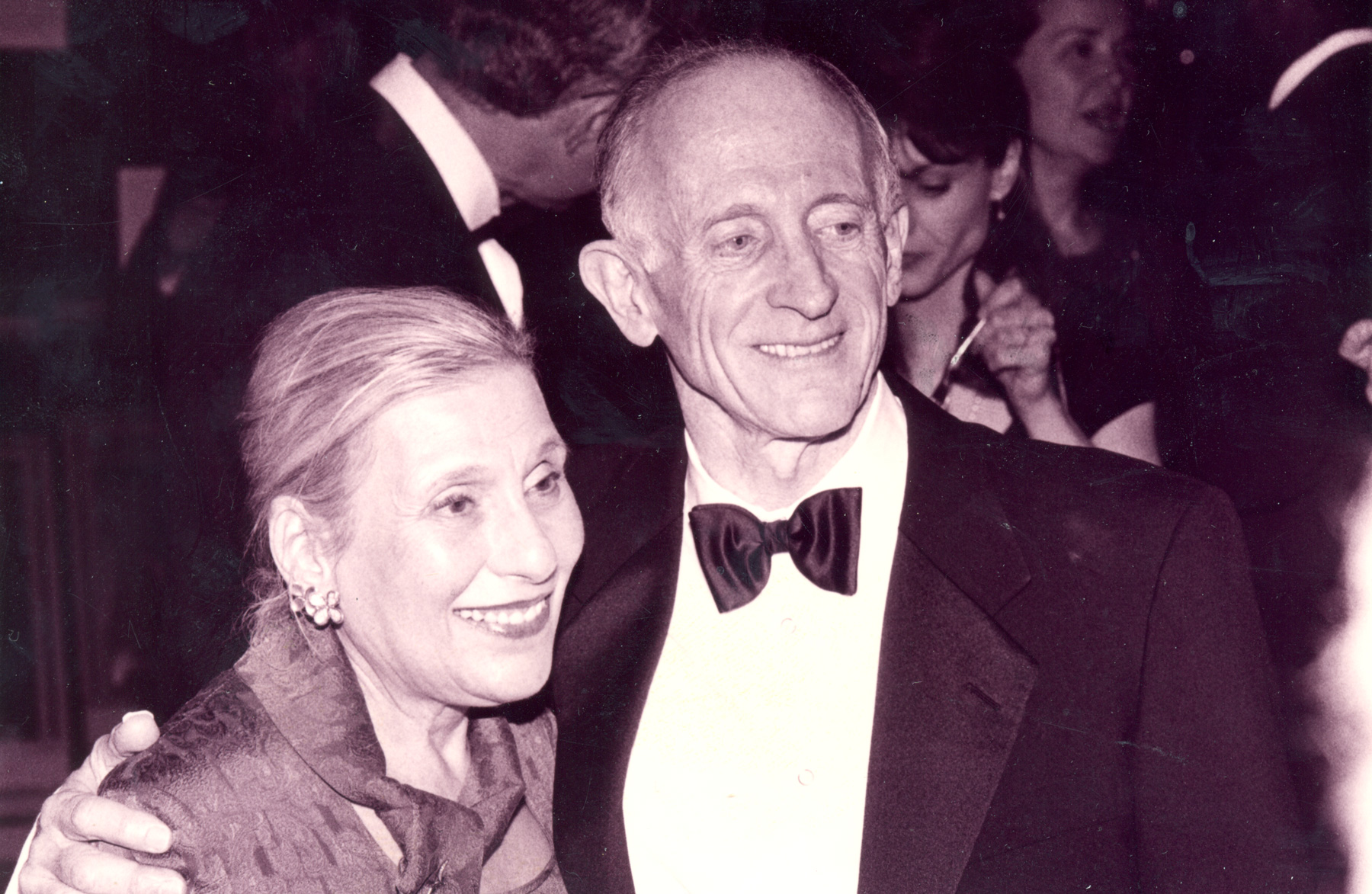

Anderson’s deep care for the planet has fueled her journey from becoming a wildlife biologist to launching the world’s first online master’s degree in sustainable design, then becoming a sustainability consultant and co-founding the Engineering For One Planet (EOP) initiative. Alongside Cindy Cooper from The Lemelson Foundation, Anderson helped launch EOP in 2020 to ensure the next generations of engineers are taught the sustainability mindsets and skillsets needed to protect and improve our planet and lives.

Over the past five years, EOP has grown into a thriving community of thousands of engineering and design faculty, students, and administrators — as well as collaborators from industry, nonprofits, government, and professional associations. More than 80 EOP grantees and subgrantees from across the country have implemented sustainability concepts and tools at their respective institutions — creating or modifying more than 600 engineering courses that have reached nearly 40,000 students.

And still more faculty from around the world have used EOP’s free resources — including the EOP Framework and companion teaching guides — to infuse sustainability and climate education into their courses and programs.

We recently spoke with Anderson about how her passion for sustainability drove an unconventional career path, and how that led to her commitment to the vision for Engineering for One Planet: that social and environmental sustainability would become a core tenet of the engineering profession, and that all graduating engineers are prepared to tackle global challenges like climate change.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Anderson studying skuas, a type of polar bird seabird, in Antarctica in 2005.

What first inspired you to pursue a career in wildlife biology?

In grade five, my teacher let us pick books we actually wanted to read, and I picked Farley Mowat’s “Never Cry Wolf.” It’s a story about living among and studying wolves in the Canadian Arctic, and about dispelling myths about the natural world by experiencing nature first-hand. It gave me real insight into what a biologist could be and could do. And so from when I was quite young, I was just determined to become a biologist and work in the Canadian High Arctic.

You grew up on a small farm in Ontario, Canada. How did you make the leap to working in the Arctic?

I grew up as a farm kid. I am the youngest of four kids, and we were the laborers on our farm along with my dad. We had to work together no matter what — even if you were mad at somebody, you still had to get the work done!

I landed my first job in the Arctic with the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1998. It really came about because I was cold calling and cold emailing — email was brand new at that time — all of these Canadian Arctic researchers. I contacted people studying seabirds, polar bears, even invertebrates. I just wanted to get to the Arctic and experience it and help in some way.

Luckily, one of the researchers also happened to grow up on a farm. I was telling him about all of my volunteer and field biology experience listed on my resume, and he just said, “It says you grew up in this little town. Tell me about that experience.” So he actually appreciated my lived experience — in addition to my work experience — because he knew that I would know what hard work meant.

I would say that I had this misinformed attitude when I was in my early career that I shouldn’t talk about the fact that I came from a small town and grew up on a small farm, that we didn’t have much money, and that I was a first-gen student. All of these things I kind of hid because I was trying to leave it behind.

But those skills I gained on the farm, they transferred perfectly into working in remote field sites with limited resources and small teams. It was a really helpful experience for me to land that first job opportunity — and realize that lived experiences are highly valuable and help to shape us and provide these incredible transferable skills to other jobs.

When did you realize that you could focus your passion for sustainability on education?

I heard Janine Benyus speak, the author of the book “Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature,” and had an ‘aha!’ moment — that I could translate my knowledge of the natural world into human design. I couldn’t believe that as a biologist, I could actually influence the people who design and build and create all the things we buy and consume and throw away.

You first worked in sustainable design education at the Biomimicry Institute and then the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD). Describe those experiences.

As one of the first hires at the Biomimicry Institute, my job was to create teaching materials for higher education to support faculty efforts to bring biomimicry into engineering, design, business, and architecture classrooms. This work was all about creating a fundamental shift to help students understand how they could look to the natural world for nature-positive design inspirations and functional strategies they could use to create new products and services.

Then in 2010, I had the opportunity to become the founding director of a new Master of Arts in Sustainable Design (MASD) program, which was at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. My job was to work with the teaching team to create the program and get the master’s degree accredited.

What lessons did you learn from your work at MCAD about building an academic community passionate about sustainability?

The faculty at MCAD were all working professionals with a depth of knowledge not only in their field, but also in sustainability. They had already been swimming upstream, trying to bring sustainability into their fields at a time that was still really early, particularly for sustainability in the professional realm and in industry.

I learned very quickly that I had this incredible roster of practicing professionals who knew way more than me about green design. I began meeting with them individually to understand their needs, what they saw as strengths of the program, and what they didn’t want to lose as we transitioned from a professional certificate into a grad program. Also, I learned what they thought made our students unique and how we could better support them.

I ultimately learned the importance of stepping back and listening, instead of charging forward and just doing what we think is the right thing to do. It’s really become the philosophy of the Engineering for One Planet initiative as well: to work with, listen to, and learn from our community.

Whether that’s co-creating the EOP Framework or other EOP teaching resources, or supporting the EOP Network, we’re always listening to and learning from our growing global community — really hearing what their needs are, what their wants are, and what their challenges and opportunities are.

How did this experience with faculty eventually help you launch Engineering for One Planet with The Lemelson Foundation?

While at MCAD, a former student of the MASD program connected me with Cindy Cooper, who was then working at Portland State University leading a program on social innovation and social entrepreneurship. I had already worked with The Lemelson Foundation through their grantee, VentureWell, on a program called “Inventing Green.” When Cindy joined The Lemelson Foundation in 2017, they were curious why environmental responsibility education wasn’t being broadly required in engineering and design programs, and whether they could do something about it.

Cindy asked me if I’d be interested in doing a discovery project where I’d be interviewing experts in sustainable design from around the world. Through this research project, we talked to people from across sectors who were working with engineering, business, and design programs, and asked them what’s working, what’s not working, what are the barriers you’re facing, what are the opportunities you’re seeing? I took on the project with a longtime colleague of mine, Dr. Jeremy Faludi, who I met through the Biomimicry Institute, and we collected data from all of the conversations and looked for patterns. The outcome of this study was the spark that helped us form what would later become EOP.

What makes EOP unique in the sustainability world, and why is it an important part of climate action?

A lot of the funding being put towards climate is going to ventures creating new technologies and services. There isn’t a lot of funding being put directly towards climate education, to help faculty bolster their knowledge and confidence to teach sustainability. We believe climate education is an effective lever to scale EOP’s impact.

We are working with the EOP community to launch a new EOP Framework companion teaching guide focused on climate education in 2026. We’re working to simplify and accelerate curricular innovation to create and scale systems-level change in engineering education. We expect that with the support of free EOP teaching resources — along with the curricular change efforts being made by the growing EOP community — we will ultimately create enough momentum where all engineering educators will have what they need to make curricular and programmatic change on their own.

What challenges is the engineering and sustainability field facing in the current moment?

Part of the nature of a community trying to change the status quo is that they are used to swimming against the current. The EOP community is used to daily challenges. They get up every day energized to work on projects they’re passionate about and that are aligned with their values.

Despite new challenges, we’re seeing many people come forward wanting to do this work and applying for funding to integrate sustainability into courses and programs. And we’re seeing more and more students advocating for these changes. We know that the green economy is still growing, and so it’s a fabulous time for engineers to be graduating. The faculty and schools we’re working with want their students to be successful when they enter the workforce, and they see green skills as a competitive advantage for their students.

What keeps you motivated in the work you do?

One of the most special and joyful things for me personally is when I present about Engineering for One Planet, and people in the audience will raise their hand and excitedly say, “I’ve been using EOP resources! I created a whole program based on it.” — and I’ve never met them or know about their program.

We’re at the point where we’ve worked with the early adopters, and now EOP is spreading on its own – it has its own momentum. So we’re looking now at how to take it to scale to achieve the EOP vision: where every graduating engineer has the skills, the experiences, and the mindsets to face global sustainability and climate-focused challenges.

Visit here to learn more about Engineering for One Planet and the different ways to connect and collaborate with the initiative.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.