From Medical Student to Tech Entrepreneur: How One Inventor is Transforming Health Care in Rural India

Through his startup company, Biosense, Abhishek Sen is helping remote communities in India get better testing for some of the country’s most pervasive diseases.

How do you solve a chronic, widespread health problem in places where money and resources are scarce?

That question led Abhishek Sen to co-found Biosense, a medical technology company based near Mumbai that designs point-of-care diagnostic equipment to detect some of India’s most prevalent and potentially devastating illnesses, including anemia and diabetes.

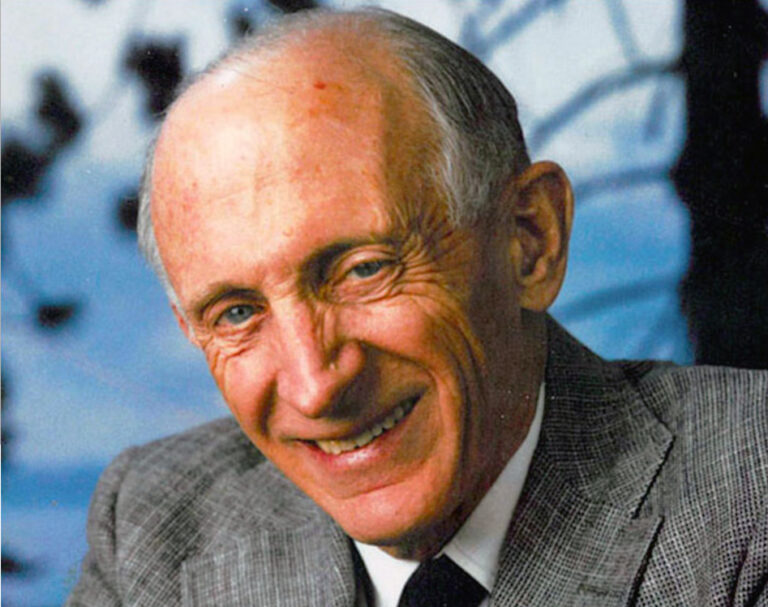

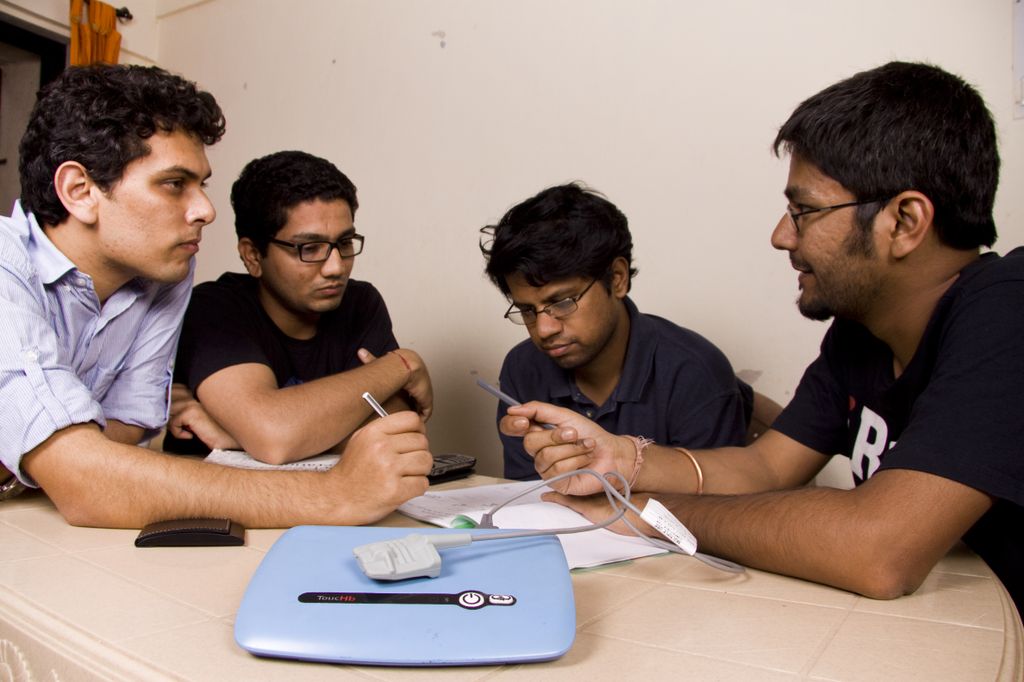

Like many tech startups, the idea for Biosense was hatched in a college dorm room. And like many inventors, Sen wasn’t picturing himself running a business when he and his classmates first began brainstorming. They weren’t entrepreneurs. They were medical students at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

But during their internships in rural parts of the country, they discovered a serious public health problem — the high rate of anemia in women, particularly those who are pregnant — and they were determined to address it.

“We started our journey with anemia,” which affects not only mothers but their children as well, says Sen. Girls born to anemic women tend to grow up to be anemic too. “So this is truly a multigenerational problem, and at some point the chain has to break.”

The problem, he says, lies not in treating the illness but in diagnosing it. “It seemed as though a lot of the cases had not been diagnosed at the right time because tools to do so didn’t exist.” Rural and sparsely populated parts of India often lack the infrastructure, electricity, and, in some cases, refrigeration needed to facilitate frequent testing. “So we thought that if we can make tools that people in rural communities can use to screen themselves, that could help.”

In 2011, after Sen and his classmates had graduated, they were selected for incubation by Villgro, India’s oldest and foremost social enterprise incubator. Through Villgro, says Sen, he and his team got the support theyneeded to make their first prototype and sale. Biosense also received downstream financial support from The Lemelson Foundation in the form of Masala Bonds, a financing tool introduced by the Reserve Bank of India in 2015 to allow foreign investors to invest in rupee-denominated bonds. A social impact investment firm and partner of Villgro – called Menterra – also provided direct equity funding for the company to develop and scale its model. This and other investment at crucial turning points helped Biosense avoid the “Valley of Death” that many startups land in.

But Biosense had plenty of bumps in the road as Sen and his co-founders grew into their newfound roles as entrepreneurs Access to working capital was a challenge. The fledgling company also ran into staffing challenges and the business learning curve was often steep. “When we started,” says Sen, “we didn’t think that we would be running a company. And over time, there are plenty of different skills that have to be picked up — from figuring out supply chain, to building a team. These are things that are not taught in medical school or that even come intuitively to most people, including me.”

So how did Sen and his co-founders make the transition? “It was challenging, but we were extremely lucky,” he says. “We’ve received a lot of help, at all the right inflection points, over the course of the last nine years.” This included a full spectrum of financial, technical and market support and mentorship.

Another key to Biosense’s success may be its perspective. As natives of India, says Sen, he and his co-founders have a clearer sense for and understanding of their clientele. “You unconsciously understand that environment better, and you’ll pick up nonverbal cues from your prospective customers better than somebody else,” explains Sen. “So I think that gives a local entrepreneur a very high edge over an expert coming in from some other country.” Decision-making and gut-checking are easier too, he says, for someone who is designing for their native context.

Last November, Biosense was acquired by an Indian diagnostics company called Tulip Diagnostics. In addition to further ensuring Biosense’s growth, the acquisition made it possible for Sen and his team to make a timely pivot as 2020 — and COVID-19 — began.

Tulip produces the Viral Transport Medium needed to ship the nasal and oral swabs used in COVID testing. But in India, like in many other countries, there was a desperate shortage of the swabs themselves.

Biosense was able to solve the supply chain problem by setting up an end-to-end production line in three weeks, along with getting regulatory approval from the Indian Council of Medical Research.

“We were able to adapt quickly because we had the resources, the factories, the labor, and a bit of raw material,” says Sen. Since the pandemic, about one out of three tests conducted in India were done on a Biosense swab, with eight million shipped to date.

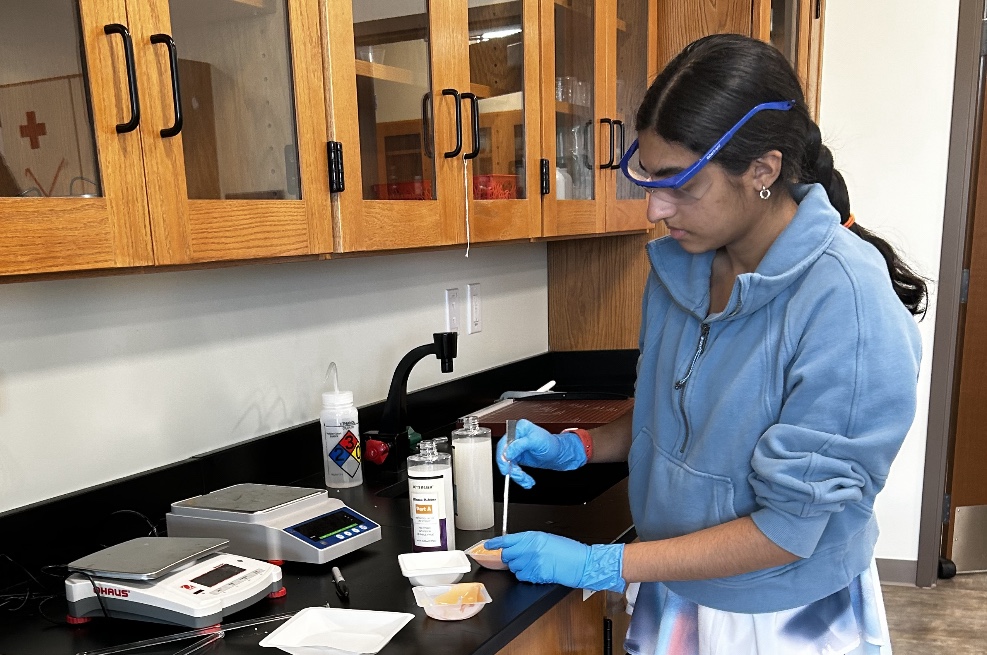

In addition to their anemia kits and COVID tests, Biosense has designed several tools to address other health problems in India, including diabetes. “We have a point of care product for urine analysis,” says Sen, “and we have a product for measuring lipids — cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL — in a finger prick.” The company also recently built a product that enables newborn screening for hypothyroidism and other common congenital anomalies.

Companies like Biosense can evolve into game-changing invention-based enterprises in the field of medical technology by solving global health challenges from a local context. This former startup is already having an enormous positive impact on the Indian communities it serves, with more than 10 million tests conducted and 5,000 mostly rural clinics served in 2019 alone.

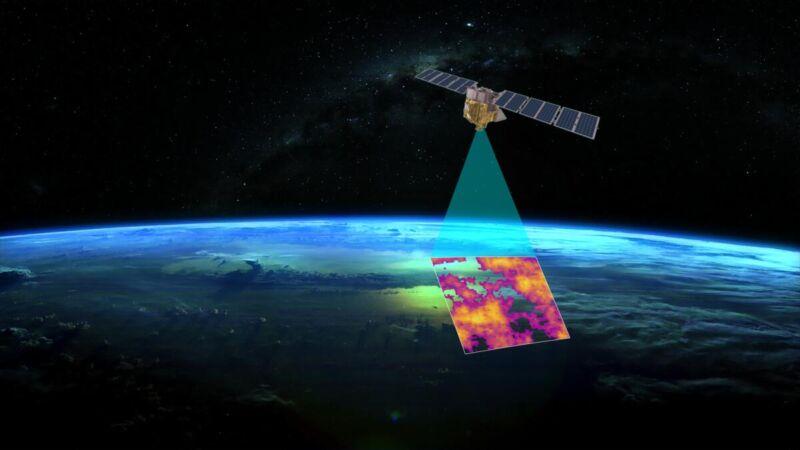

For one thing, its tools are affordable. For another, screening happens right in the village where people live, and data is sent to the cloud, making it possible to monitor residents’ health. This setup, says Sen, is effective because testing at the local level with inexpensive devices can lead to earlier detection of disease, which lowers the cost of treatment and reduces the burden on the health care system.

In the case of anemia, where the Biosense journey began, there is hope of breaking the chain that Sen and his co-founders first observed as medical school interns. If you can routinely test and monitor, he says, “you can actually see the macro trends of hemoglobin improving. That gives that community hope. We have stronger children, and we have stronger mothers giving birth to stronger children.”