From Plastic Surgeon-in-Training to Inventor: How a Family Tragedy Led One Latina to Improve Lung Disease Diagnosis for the World

min read

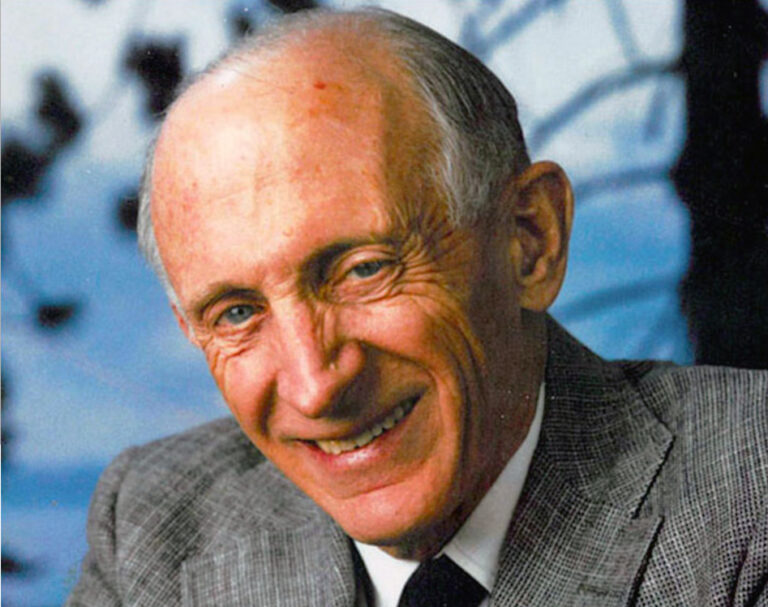

Maria Artunduaga, CEO & Founder of Samay.

Maria Artunduaga is the CEO and founder of Samay (formerly Respira Labs), a successful startup aimed at providing low-cost, at-home diagnostics for dangerous respiratory conditions.

At age 34, Maria Artunduaga took a leap of faith. Ambitious and focused, she was studying plastic surgery — a highly competitive specialty — at University of Chicago Medicine, on track to become a reconstructive plastic surgeon for children.

Then, back home in her native Colombia, Artunduaga’s beloved grandmother, Sylvia, died.

The cause of death was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, a condition involving constriction of the airways and difficulty breathing. In addition to being brokenhearted, Artunduaga and her family were frustrated that there were no ways for respiratory patients to monitor their lung function outside of a hospital.

So Artunduaga made a radical decision. She abandoned her career in clinical medicine to start a company centered on a solution for the problem that took her grandmother’s life.

She enrolled in engineering school and made the switch from surgeon to CEO. With the help of incubators like VentureWell’s E-Team and ASPIRE programs, the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps (I-Corps), and grant funding from the NSF and the National Institutes of Health, she hit upon a novel idea — to develop a device that uses sound to detect respiratory issues before they become life-threatening emergencies by harnessing the power of acoustics, inspired by her husband’s work at Google.

We spoke with Artunduaga about the impact of invention, the future of her technology, and her passion for inspiring the next generation of female entrepreneurs.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your journey from doctor to inventor.

I’m originally from Colombia — I trained as a physician there and relocated to the U.S. in 2007. My dream back then was to become a reconstructive plastic surgeon for kids. I was inspired to do that because of my little sister. She was born preterm and developed cerebral palsy so had to undergo a lot of reconstructive surgery.

But while I was in Chicago my grandmother, who I was very close with, died from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD. My family and I were far away and despite us calling every day to try to help her gauge how she was doing, we just couldn’t make a diagnosis in time. She got worse, and it was too late. She had to be admitted to the ICU. Two weeks later, she died from complications.

That’s when I took a leap of faith. I retrained entirely and earned two master’s degrees. I’m 41 now and I have no regret whatsoever to have made that decision because I’m fulfilling my long-term goal of helping people through my work. You don’t necessarily need to be seeing one patient every 20 minutes to create an impact. I’m doing it through invention — creating technology, and ideally, helping millions of people at a time.

How did you make the switch from the operating room to the boardroom?

Some of it has been luck and serendipity. I happen to live in the Bay Area. I happened to be completing my master’s degree at Berkeley, which happens to have a business school. But in my entire life, I never envisioned starting a business. I couldn’t see myself dealing with money, finances, or sales. Then I discovered that creating a business is exactly like following the scientific method. It’s mainly qualitative research, and I found that fascinating — you have a hypothesis, you have to test that through interviews.

And the other thing is, as a doctor, I’m very good at finding connections amongst unexpected things, like disciplines or parameters. I’m a good diagnostician, especially coming from a middle-income country. In Colombia we don’t have a lot of technologies that are available here in the States, so we’re very good at using our heads to diagnose something. That’s sort of my superpower.

What COPD challenge were you trying to solve?

Ideally, we are trying to solve a problem that killed my grandma, which is to make a diagnosis that’s early enough so that medical interventions can be implemented at home. This way we help keep patients out of the hospital, where they are prone to complications like infection.

In the U.S., COPD is the third leading cause of death. It affects about 30 million Americans, yet only half of them are diagnosed. And beyond COPD, we have asthmatics and COVID patients. Asthma affects many younger patients, also, 40 percent of patients who have gone through COVID and survived still report difficulty breathing up to even six months later.

Right now, the main challenge that respiratory patients have is that the clinical standard is to use a questionnaire to make a diagnosis of pulmonary function decline.

I’m trying to solve this problem by creating a quantitative tool for patients that can give them accurate, medical grade information about their lungs, non-invasively, easily, and consistently. Medicine has innovated to create similar tools for other conditions, like arrhythmia and diabetes, but for pulmonary diseases, we literally have nothing other than the pulse oximeter. But the problem with the pulse oximeter is that it gives you a reading of the oxygen levels in your blood, which is not a direct parameter to the amount of air that is coming in and out of your lungs. Basically, when you hit an abnormal number on your oximetry, it’s too late, and the patient has to be in the emergency room. So that’s the problem.

What is the device that you created, and how does it work?

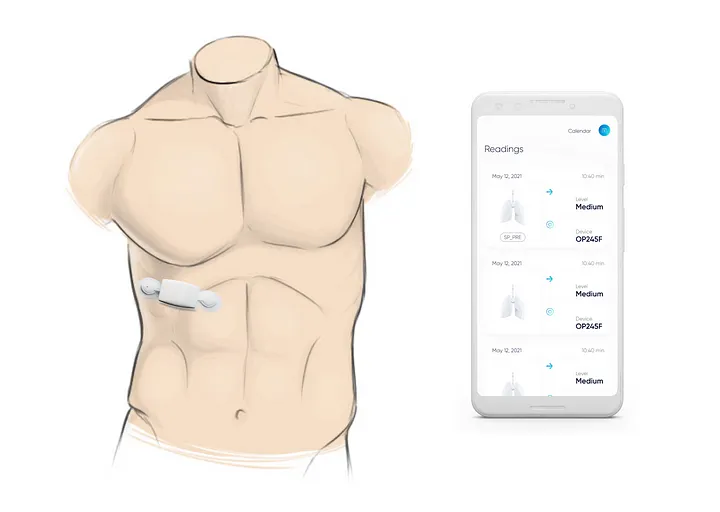

Our device — named Sylvee, after my grandmother — is a prototype, and it’s modeled after continuous glucose monitoring sensors. The technology is essentially a repurposed hearing aid for tinnitus — my mom is an ENT surgeon so we discussed the idea of using it for the lung. Think of speakers and microphones that you find in your headphones or hearing aids, but instead it affixes to your chest and on the lower ribcage. It injects sound through the thoracic cavity and listens back to it and captures changes in resonance.

How did you come up with the idea to use sound as the diagnostic?

The resonance of the chest should stay the same unless there is an abnormal volume of air staying in. And what we know in medicine is that when a patient is declining or their disease is getting worse, the lungs start trapping air.

Air-trapping, like a fever, is a biomarker, or a biological sign that there is an abnormal process occurring in the body. Thus far, we haven’t been able to actually use air-trapping in clinical medicine because the only way to measure it is through CT scanning. So by sending a signal and listening back to it, we can see the acoustic resonance signatures and actually flag any abnormalities.

I’m not an engineer, and I’m super clinical, so I started backwards — asking what is the problem, what’s the clinical need? And, how can we solve this by using technology that’s already out there, instead of spending 10 years trying to do basic science? That’s how we decided to repurpose acoustics.

What stumbling blocks did you face on your path to invention?

First, learning biomedical engineering from scratch — understanding firmware, hardware, design, and like, what the heck is a PCB (printed circuit board)? Showing up with vulnerability is probably one of the hardest things to do. I tell my consulting engineers, look, I’m a physician. I’m going to ask you very stupid questions, but please, bear with me. So that’s one of the main challenges.

And again, I had never started a business before. So every single day, I’m learning, and this is a process. As a doctor, I tried to never make a single mistake because people’s lives were at risk. So changing that mindset, and rewiring my brain, that was definitely the hardest part of all.

What’s the status of your device now?

Right now we’re building a generation two device with hardware engineers in the U.S. and software developers back in Colombia, and we’re validating the working prototype against the clinical standard, which is a hospital-based test where you blow through a big machine called a plethysmograph.

We’re placing our device on the patient’s chest at the same time and trying to figure out the associations that we see between acoustic frequencies from our device and the actual numbers that we’re getting from the machine. We’re doing this with COPD patients, severe asthmatics, and COVID patients who still have symptoms after 28 days. The plan for 2022 is to do this with 200–500 patients. I’m setting up additional collaborations with two Colombian hospitals.

Do you foresee this working in low- and middle-income countries?

That’s my ultimate goal. And it’s why we decided to repurpose low-cost sensors — because the research that’s out there has used portable ultrasound to detect air trapping, and the problem with those is that they cost roughly $2,000, and that is way too expensive. So we decided to use cheap components to make low-cost patches that when mass-produced, should only cost around $25, probably even less. With a device that is affordable, we definitely envision going anywhere, literally, throughout the world.

What kind of role model would you like to be for other women entrepreneurs and inventors?

I really want to inspire women, especially to take the risks that are necessary to forge their own paths. As women, we are taught that we need to be perfect, that we need to be very careful about the decisions that we make in life. And starting a company is risky, professionally and financially — up to 80 percent of startups fail. And that fear of failure is what is holding us back, but I want more women to just do it.

I’m very open, I’m always sharing my challenges. I faced discrimination in the U.S. as an immigrant Latina with a lot of drive. And as a woman growing up in a machista culture, there weren’t any role models — very few women had post-graduate training. I had the only doctor mom in the entire school, and I wanted to become like her. So that’s probably why I’m the way I am.

I think information is extremely powerful. And people need to have access to the information; like, how I did this, how I approached it, how I failed, what I learned. I want to give this recipe to a million little girls so that, 10 to 15 years from now, they can do the same thing.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.