How Two Sustainability-Minded Inventors Are Changing the Way Food Could Be Grown in the Future

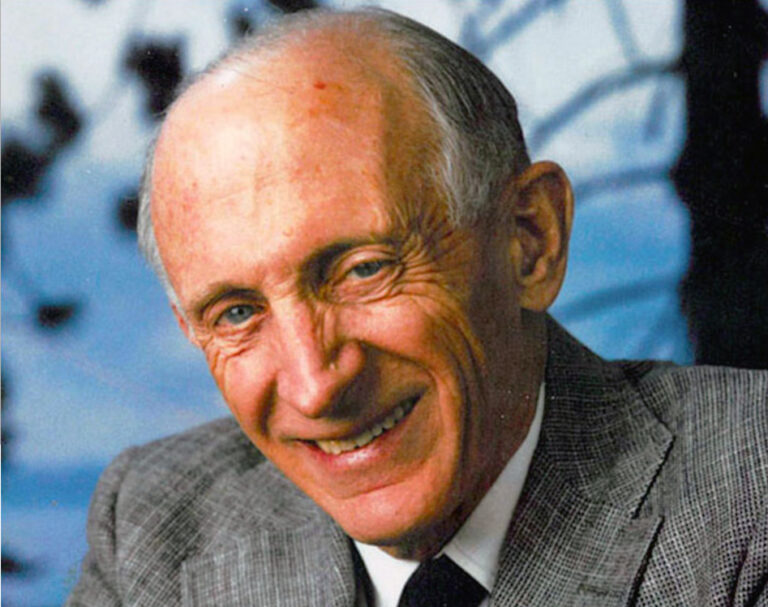

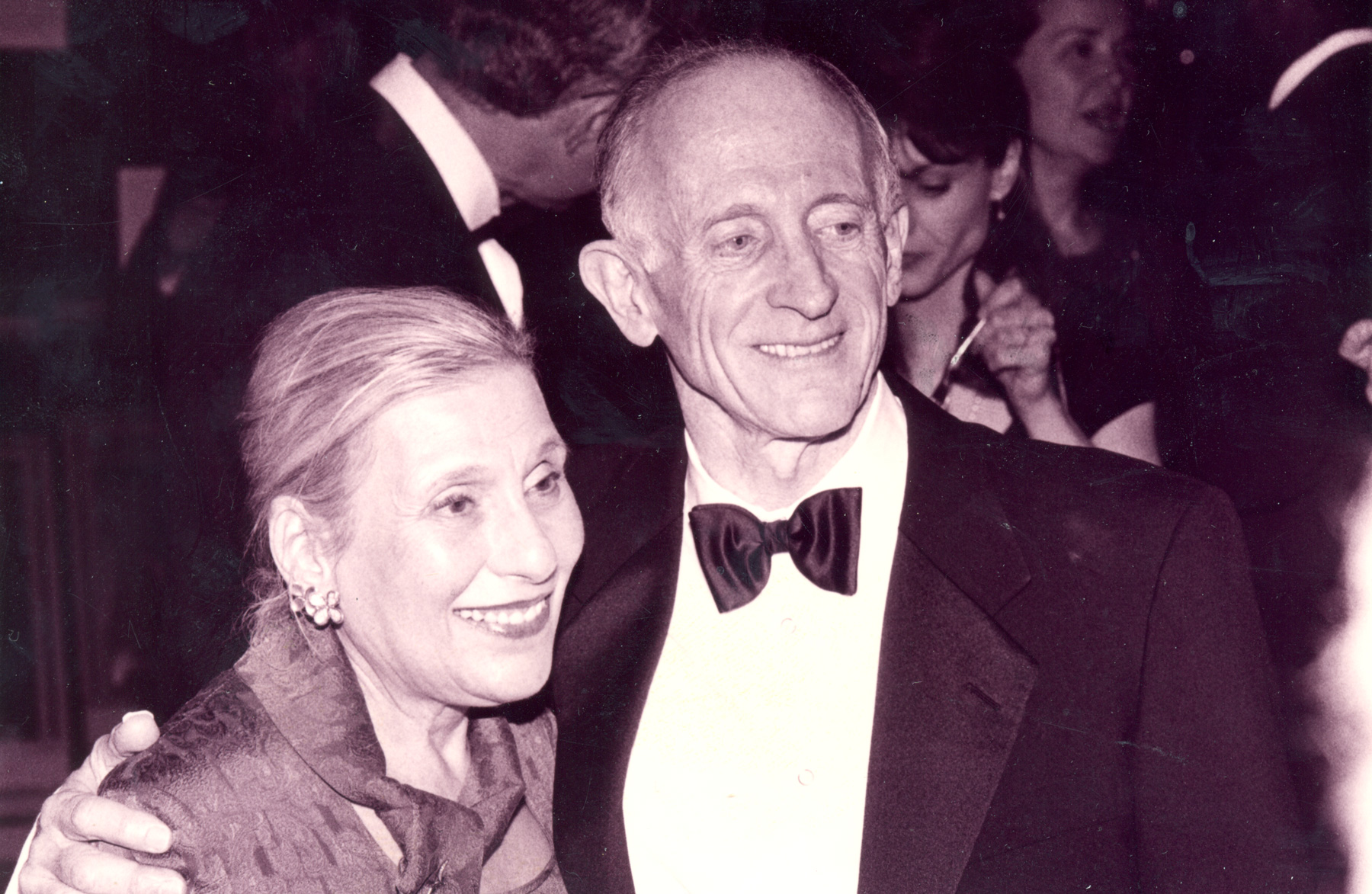

Skyler Pearson and Hugh Neri are striving to make vertical farming more effective – and more affordable – through their innovative company, Nexgarden

Skyler Pearson and Hugh Neri of Portland, Oregon, are not your typical farmers. They’re inventors and entrepreneurs, and they spend much of their time in front of computers, on a quest to create sustainable alternatives to traditional agriculture. Pearson and Neri own Nexgarden, a commercial vertical farming company that grows leafy greens and other vegetables for local restaurants and grocery stores.

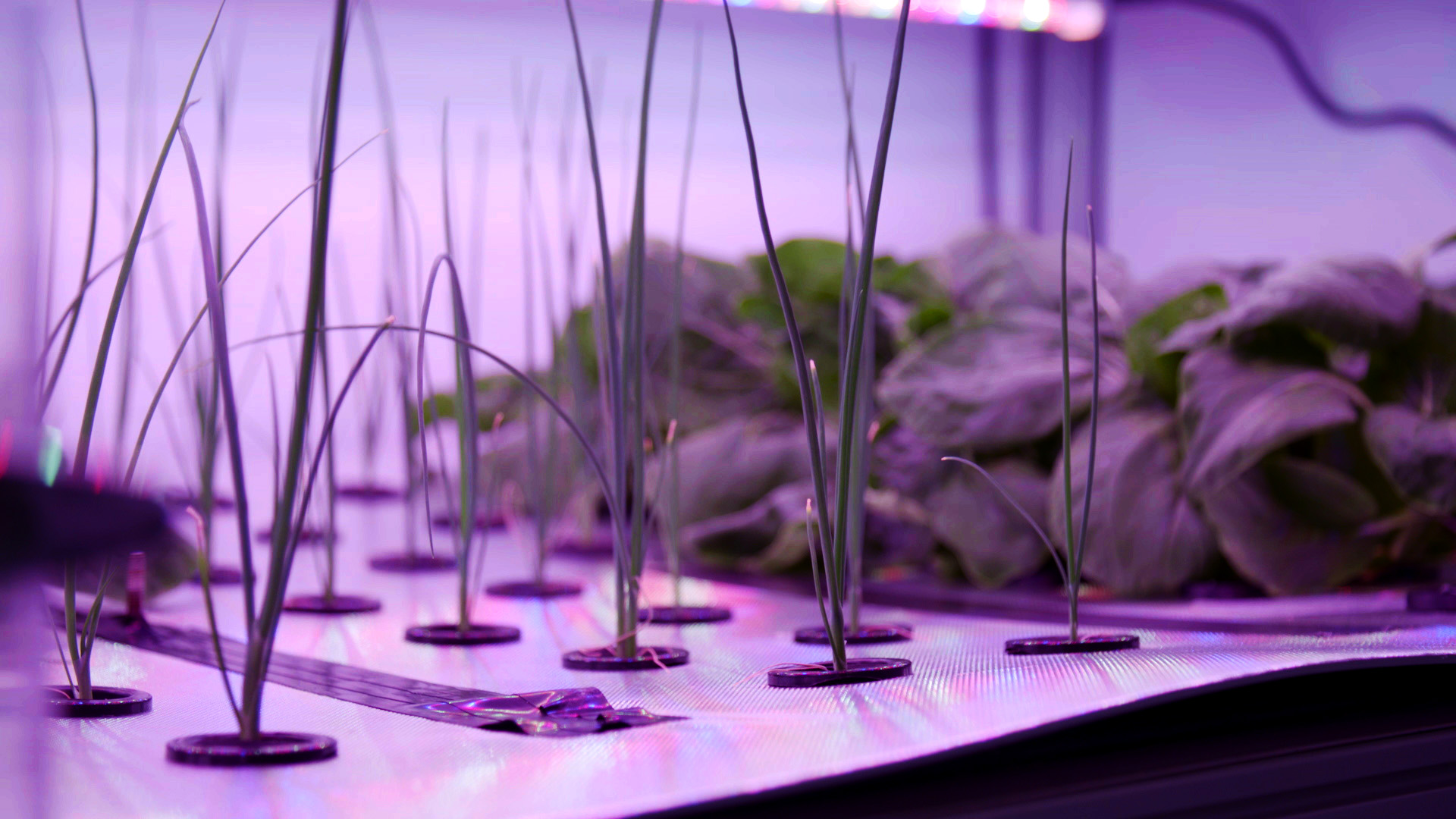

Like other vertical farms, Nexgarden uses a fraction of the water needed in conventional irrigation and requires zero pesticides. But instead of sticking with generic building configurations, Pearson and Neri designed Nexgarden to be more energy efficient and support a wider range of crops under one roof than standard vertical farms.

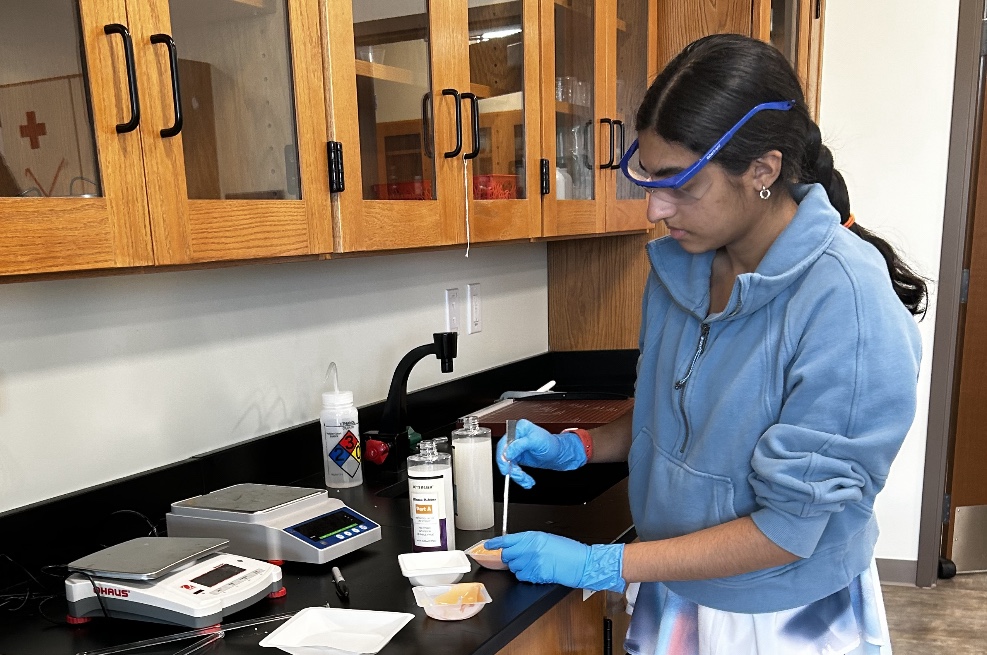

The Nexgarden growing method is based around a high pressure aeroponics system. Unlike hydroponics — which requires plants’ roots to be submerged in water — aeroponics involves exposing roots to the air and spraying them with a nutrient-rich solution.

“Our high pressure aeroponics is unique because it sprays the plants’ root systems at specific intervals with a super-fine mist of nutrient solution, which allows the plants to uptake the nutrients they need while also getting enough oxygenation in their roots,” says Neri. “That combination makes for really fast and robust growing and lots of good, strong flavor within the plants.”

Neri was in grad school at Portland State University when the idea for Nexgarden first took hold. During his time in the school’s sustainability and social entrepreneurship programs, students were tasked with taking an idea for a social enterprise and developing it into a fully functioning business model.

“I was intrigued by vertical farming at the time and was wondering why that wasn’t how all plants are grown,” says Neri. So he and Pearson decided that they would focus on finding the best and cheapest way to build and operate a vertical farm, in hopes of attracting a wider audience to the method.

They entered their idea in an intra-school sustainability competition called The Clean Tech Challenge, and won a cash prize. With the money, they built a prototype and then entered that prototype in the statewide innovation competition, Invent Oregon, in 2017. They won again.

After that, Pearson and Neri began building their business in earnest. “We used the money from our Clean Tech and InventOregon wins to develop our patent,” says Pearson. “After that we decided to kind of bootstrap and pay our own way to a larger prototype that would produce enough food for us to start to sell it.”

They called their former mentor from the Clean Tech Challenge, Jeff Brown, who is the general manager of two restaurants at The Nines Hotel in Portland, and told him about their prototype and that they were looking for a place where they could store and operate it. Brown had a lab in the basement of his restaurants and the plan — to set up a farm in Brown’s basement and grow produce for his restaurants — clicked. “It was kind of a no-brainer,” says Neri.

From the start it was a mutually beneficial arrangement. “When we harvest, we literally just bring it right upstairs,” says Pearson. And for the restaurant, this freshness translates to a longer shelf life and significantly better flavor than produce that’s shipped from farther away.

But the need for local and indoor farming goes far beyond fine dining. First of all, says Neri, the methods used in vertical farming — like hydroponics and aeroponics — all radically reduce water consumption. “Our aeroponics system actually uses 99 percent less water than an outdoor farm would because we’re able to recirculate the water and the only water that’s lost is through evapotranspiration from the leaves of the plant.” Nexgarden’s technology also uses about a third of the fertilizer that an outdoor farm would use and no pesticides whatsoever.

Climate change is a key driver for them, says Pearson. “The land that we have is slowly going away, and the population is increasing at a rate that current farming methods aren’t going to be able to sustain.” As climate change inevitably leads to more droughts and pest problems, growing food outdoors will become more challenging, which will put farmers’ livelihoods in jeopardy. “There’s going to be a lot less room for error if a single hurricane or drought comes through and an entire crop is lost,” she says.

So if vertical farms solve for so many problems, why aren’t there more of them?

“At the moment,” says Neri, “hydroponically and aeroponically grown vegetables are a pricey commodity.” Building and operating a vertical farm is expensive, and those costs translate to high prices for the produce they generate. But even this problem can be overcome.

They hope to eventually shift the indoor farming paradigm so that its prices are comparable to those of conventionally grown produce. “I think there’s a ton of room for improvement in terms of making it affordable for the masses,” says Neri.

For now, the only produce that Nexgarden sells commercially are leafy greens. But Pearson and Neri are constantly experimenting, which helps them figure out their limitations, they say. Some of their successful trials include bok choy, beets, radishes, green onions, basil, mint, and a variety of other herbs.

“What Hugh and I both really want is to build something powerful enough to make a difference,” says Pearson. “Something that could create a whole new segment within commercial agriculture — something that’s going to be better for the environment, and better for, you know, the people of the world.”