This Former Rugby Player is Now a Game-Changing Inventor

Personal experience drove Jessie Garcia to create her novel head impact indicator.

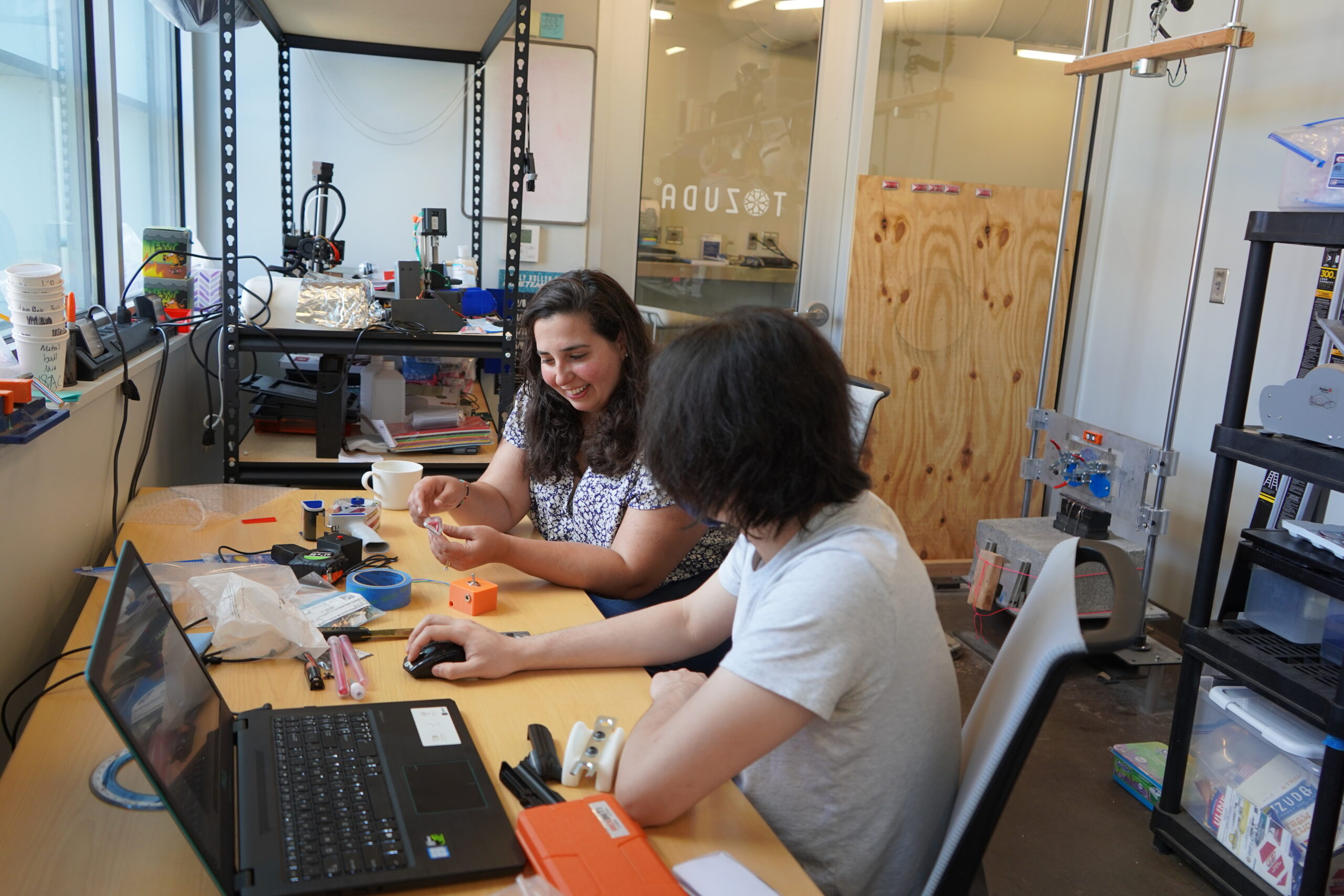

Identify a problem, then work to solve it. That’s the basic formula for invention, and that’s exactly how Jessie Garcia came to create the Tozuda Head Impact Indicator, a tiny tool that attaches to a helmet and signals to its wearer when a significant impact has occurred.

Spanish for “hard-headed,” the name Tozuda is an affectionate nod to Garcia’s grandmother, who Garcia has always been close with and seen as a role model. “My abuela used to call me tozuda growing up,” she says. “I thought it was really, really fitting.”

Tozuda’s Head Impact Indicator signals to its wearer when a significant impact has occurred.

Garcia’s invention is seemingly simple. Measuring about two inches by one inch, the clear rectangular device attaches — with aerospace-grade tape — to the back of any helmet. When a user’s head is hit hard enough to require medical attention, the device’s nonelectric mechanism shifts from clear to bright red. “If it’s red, check your head,” is the catchy company tagline. Credit for that goes to Garcia’s father, she says. “He’s the marketing genius behind our slogan.”

A first-generation Cuban American, Garcia grew up in New Jersey and played rugby in high school. She continued playing in college at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, until she sustained a concussion in 2010. It left her symptomatic for six months, interfering with reading and writing and causing a sensitivity to light.

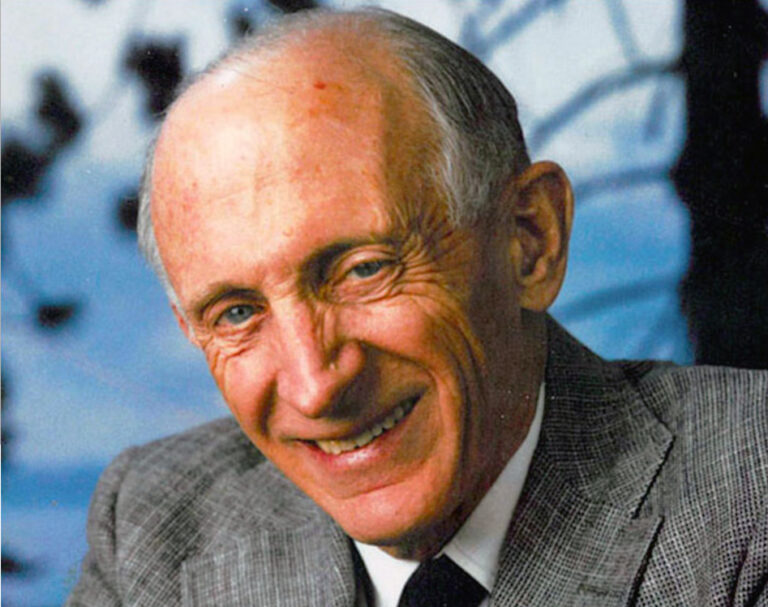

A first-generation Cuban American, Jessie Garcia is the Founder of Tozuda.

At the time, the only concussion-detection device on the market was a mouth guard for $300. “As a college student, it’s something I simply couldn’t afford,” she explains. “I used to go through three or four mouth guards a season.”

After graduating, Garcia went on to earn her master’s in technical entrepreneurship, and it was around this time, in 2013, that the idea for Tozuda began to click. She started digging into available data and research on concussions and quickly realized her situation wasn’t unique.

According to Garcia, the CDC estimates that there are as many as 3.8 million concussions and traumatic brain injuries from sports and recreation in the U.S. each year, with a high percentage of those going undiagnosed. “I started becoming a little obsessed with the problem,” she says, “and going out and talking to other players and coaches and teams and just learning more about what could be helpful.”

Her first attempt at a solution was to build a less expensive version of a mouth guard detector. She quickly scrapped that idea after getting feedback from athletes who found mouth guards troublesome. “Everyone’s feedback — from hockey players, football players, softball, and baseball — was, ‘Can I just put it on my helmet?’ So that gave me direction.”

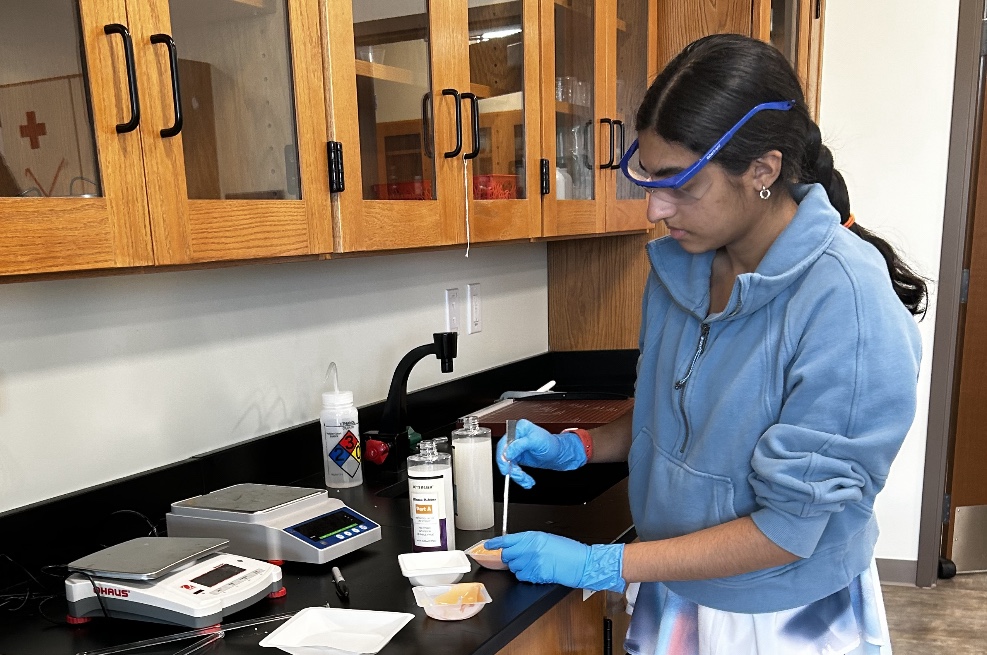

Garcia began iterating on a mechanical device without electronics to help keep costs low. She developed a mechanism which detects force of impact and, when the impact is strong enough to potentially cause a concussion, releases a red dye into a clear chamber.

From there, Garcia spent a lot of her own time and money on bringing Tozuda to life, as well as to the market. Those were difficult years for Garcia. After graduating with her master’s, she no longer had access to a maker space. She moved into her parents’ house in New Jersey and enrolled in a community college where she could have access to the software and tools she needed to continue working on her invention. One of the first things she saved up for? A 3D printer.

Eventually Garcia moved to Philadelphia, where she and Tozuda CTO Chris Basilico found a maker space she could use to begin fabrication. “I was only getting so far with 3D printing,” she says. For a while, they used a vintage injection molding machine they’d bought on eBay that they affectionately named Bertha. But ultimately it gave out, and they knew they needed funding.

The turning point was a grant from Protolabs, a well-known prototyping injection molding company. “That was just such a game changer,” Garcia says. “We didn’t have access to capital at that time, and that really changed the narrative for our company.”

In 2019, Garcia fulfilled a Kickstarter campaign that allowed her to bring her first patented prototype to market. They incorporated early feedback and released an improved second version in February 2020.

Like many startups, she had to contend with the adverse effects of the pandemic. Supply chain disruption dramatically increased their lead time for parts. “And to see the world stop — and sports stop — I thought, ‘What are we going to do?’

What they did was buckle down and enter new markets for essential workers like the construction industry, and recreational sports like biking. Today her users are wide-ranging, including hockey and football players, as well as oil rig workers and even the United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force bobsled team.

She ultimately attributes the long-term success of Tozuda to persistence — fueled both by working on an issue she is passionate about, and the example set by her family, who immigrated from Cuba. “My family sought out a better life in the U.S., and they found entrepreneurship to be their driver to success,” she says. “I saw how hard they had to work for a dollar.”

The United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force bobsled team uses Tozuda’s Head Impact Indicator (courtesy of RAF).

To other aspiring inventors, she offers a few bits of advice: “Start with what you have. If what you have is a pen and paper, that’s further than the person who’s just left it up in their head.”

She also emphasizes finding the right people to work with and not worrying too much about others’ opinions. “I’d rather be underestimated,” she says, “and then just kill them with competence.”

And finally, it’s important to remember that invention, like many sports, can require resourcefulness and patience. “Get scrappy until you can move faster,” she says. “It’s an endurance game, not a sprint.”