Meet the Woman Who Forged an Entirely New Scientific Field

Chemical biologist Carolyn Bertozzi is blazing a trail in the way cancer and other diseases may be diagnosed and treated.

Picture a peanut M&M, cracked in half. That candy cross section can be a helpful visual for remembering the basic structure of a human cell. The nut of course represents the nucleus at the cell’s center. And the chocolate represents various fats and proteins that surround it. But it’s the exteriors of the cell and the candy that really invite comparison — because both are coated in sugar.

Chemical biologist Carolyn Bertozzi remembers learning this as an undergraduate at Harvard University. Now a professor of chemistry and biology at Stanford University, she continues to refer to the human cell-M&M analogy as a jumping off point for talking about her work.

And for good reason. Bertozzi’s research involves studying the sugar molecules — or glycans — on cell surfaces, and how these surfaces differ depending on disease. If a healthy cell surface is like a well-manicured garden, says Bertozzi, then the surface of a cancer cell is like an unruly jungle. And the overgrowth is made up of a specific glycan called sialic acid.

But why the overgrowth? And then, how can a better understanding this phenomenon lead to earlier detection and treatment of cancer and other illnesses?

Bertozzi and her students are endeavoring to solve these mysteries at her Stanford lab, dubbed the Bertozzi Group, and Stanford’s interdisciplinary institute ChEM-H (Chemistry, Engineering & Medicine for Human Health). The study of glycans from a chemical or biological perspective is known as glycoscience. It’s central to Bertozzi’s work, and central to certain transformative cancer treatments, such as immunotherapy. Her goal is to improve humanity’s understanding of how glycans react with healthy and diseased cells — and to create new methods and technologies for interacting with and exploiting these chemical reactions in order to invent novel diagnostics and treatments.

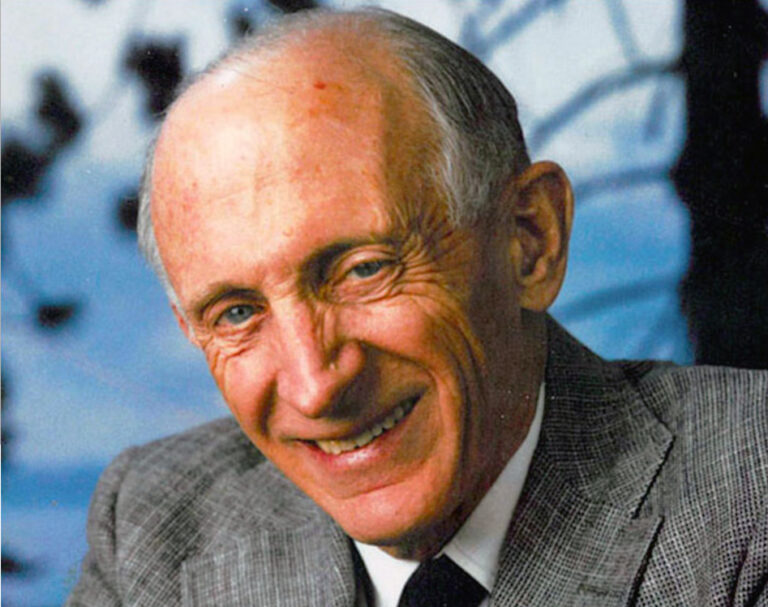

Her unique approach, which involves creating controlled reactions within cancer cells and zebrafish, has led to the establishment of an entirely new scientific field, called bioorthogonal chemistry. The 2010 Lemelson-MIT Prize Winner, Bertozzi has published hundreds of scientific articles from her groundbreaking research, holds more than 60 patents and has also co-founded seven biotechnology companies.

Many of these companies and papers reflect collaborations with her students. A beloved and highly-regarded mentor, Bertozzi is known to inspire elementary school-age children and postdoctoral fellows alike. Her Stanford website features congratulatory messages to students who have gone on to open their own labs, publish articles or achieve other success.

Bertozzi’s innovations in bioorthogonal chemistry have already led to advances in medicine that are resulting in new technologies and new drugs for everything from cancer to tuberculosis to COVID-19. Or, as she puts it on her website, “roadmaps for creating synthetic forms of life engineered to serve human needs.”

Learn more about the social and economic impact of invention through the RAND report “Measuring the Value of Invention,” documenting twenty-five years of the Lemelson-MIT (LMIT) Prize.